|

| The News Line Tuesday February 28 2012

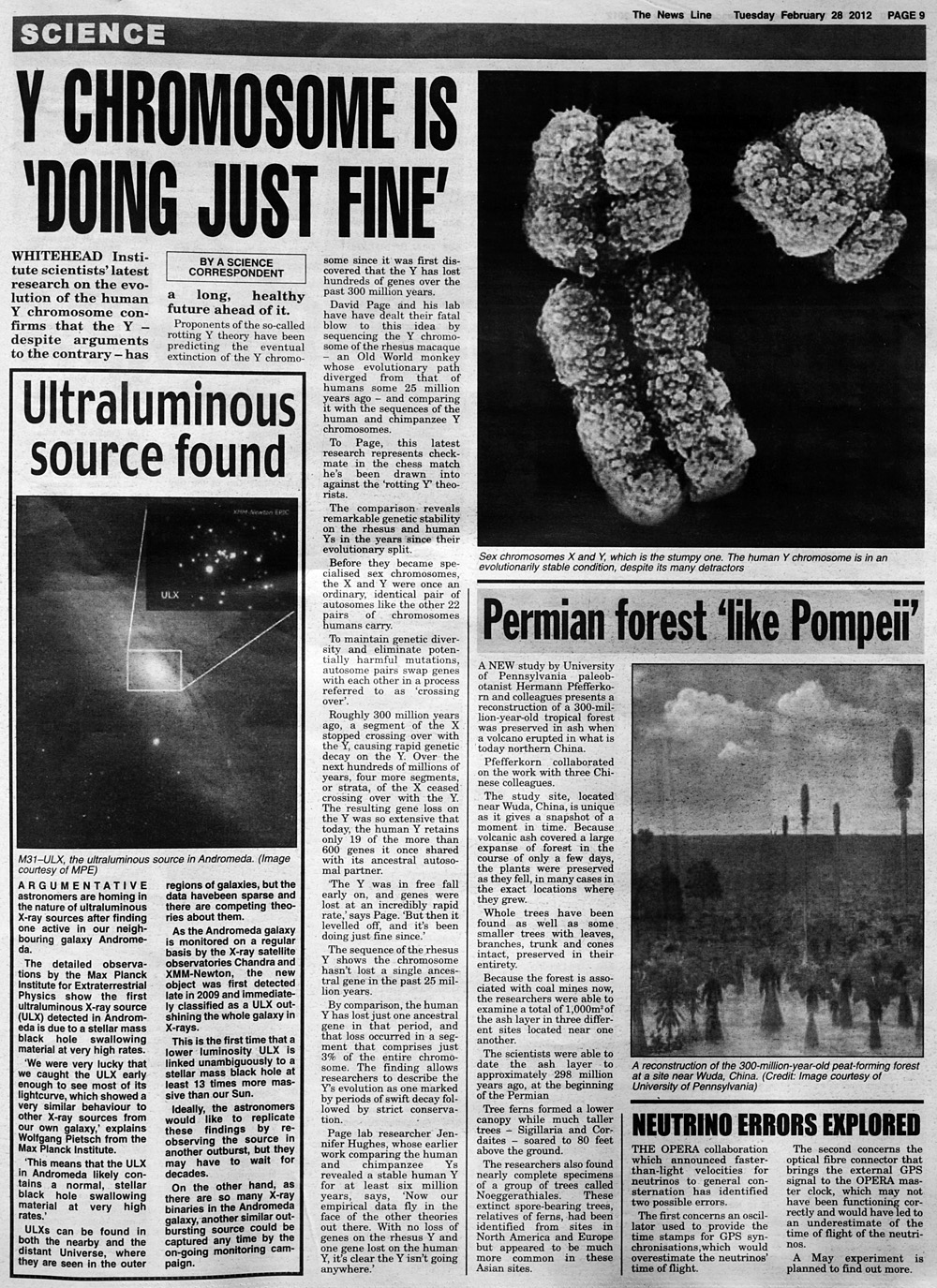

PAGE 9 SCIENCE Y CHROMOSOME IS 'DOING JUST FINE' BY A SCIENCE CORRESPONDENT WHITEHEAD Institute scientists' latest research on the evolution of the human Y chromosome confirms that the Y - despite arguments to the contrary - has a long, healthy future ahead of it. Proponents of the so-called rotting Y theory have been predicting the eventual extinction of the Y chromosome since it was first discovered that the Y has lost hundreds of genes over the past 300 million years. David Page and his lab have dealt their fatal blow to this idea by sequencing the Y chromosome of the rhesus macaque - an Old World monkey whose evolutionary path diverged from that of humans some 25 million years ago - and comparing it with the sequences of the human and chimpanzee Y chromosomes. To Page, this latest research represents checkmate in the chess match he's been drawn into against the 'rotting Y' theorists. The comparison reveals remarkable genetic stability on the rhesus and human Ys in the years since their evolutionary split. Before they became specialised sex chromosomes, the X and Y were once an ordinary, identical pair of autosomes like the other 22 pairs of chromosomes humans carry. To maintain genetic diversity and eliminate potentially harmful mutations, autosome pairs swap genes with each other in a process referred to as 'crossing over'. Roughly 300 million years ago, a segment of the X stopped crossing over with the Y, causing rapid genetic decay on the Y. Over the next hundreds of millions of years, four more segments, or strata, of the X ceased crossing over with the Y. The resulting gene loss on the Y was so extensive that today, the human Y retains only 19 of the more than 600 genes it once shared with its ancestral autosomal partner. 'The Y was in free fall early on, and genes were lost at an incredibly rapid rate,' says Page. 'But then it levelled off, and it's been doing just fine since.' The sequence of the rhesus Y shows the chromosome hasn't lost a single ancestral gene in the past 25 million years. By comparison, the human Y has lost just one ancestral gene in that period, and that loss occurred in a segment that comprises just 3% of the entire chromosome. The finding allows researchers to describe the Y's evolution as one marked by periods of swift decay followed by strict conservation. Page lab researcher Jennifer Hughes, whose earlier work comparing the human and chimpanzee Ys revealed a stable human Y for at least six million years, says, 'Now our empirical data fly in the face of the other theories out there. With no loss of genes on the rhesus Y and one gene lost on the human Y, it's clear the Y isn't going anywhere.' http://www.wrp.org.uk |